By Steve Price

They carried names like Crusader, El Capitan, Silver Star and Sunbeam. Their sleek, aerodynamic designs and colorful paint schemes drew crowds to train stations all over the country. Passengers enjoyed scenic views of America’s picturesque landscapes in unequaled comfort and style. But all good things must come to an end, and the glory days of this wondrous trainset were numbered with increased competition from other forms of travel. And then, with the snap of the government’s fingers, they began to disappear from the country’s railways altogether.

For almost thirty years, the United States enjoyed some of the finest rail travel in the world aboard streamliners, trainsets that were designed in shape to minimize air resistance, greatly increasing their speed. They we the belles of the proverbial ball, designed to be as aesthetically pleasing to the eye as they were fast in order to attract rail passengers during the hardships endured during the Great Depression. Their delivery to the railways marked a period of unequaled style and luxury in American passenger rail service.

The first streamliner was delivered for the Union Pacific rail company on February 25th, 1934. Named the M-10000, it was a vividly painted Winton distillate engine with top speeds of over 100 MPH; its three car consist included the combined power car, railway post office and baggage compartment with a sixty-seat coach car and an observation and buffet car with seating for 54. Despite issues with its 600 horsepower engines, the publicity generated from the arrival of the M-10000 generated great success for the Union Pacific.

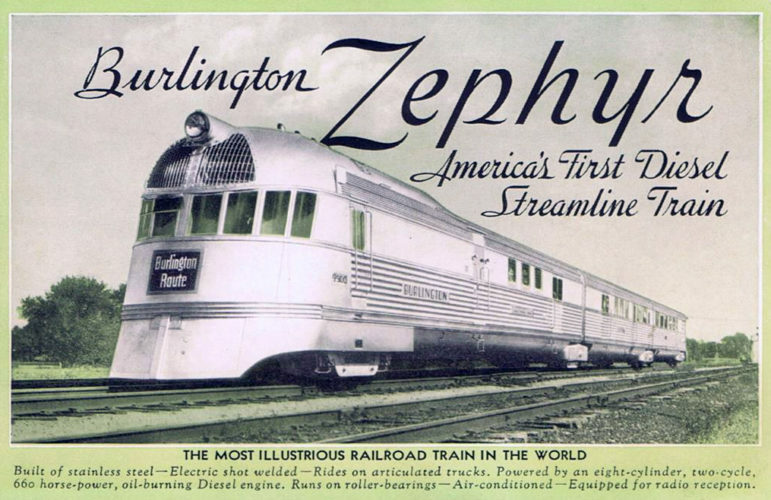

Other streamliners were soon to follow, including the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy’s famous Burlington Zephyr (later renamed the Zephyr 9900 and then the Pioneer Zephyr). Unlike the M-10000, the prime mover for the Zephyr was a 600-horsepower diesel-electric engine, which proved to be more reliable than its counterpart running on the Union Pacific. It achieved great fame and notoriety on it May 26th, 1934, when it made its famous “Dawn to Dusk” travel between Denver, Colorado and Chicago Illinois – a distance of over 1,000 miles.

Other streamliners were soon to follow, including the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy’s famous Burlington Zephyr (later renamed the Zephyr 9900 and then the Pioneer Zephyr). Unlike the M-10000, the prime mover for the Zephyr was a 600-horsepower diesel-electric engine, which proved to be more reliable than its counterpart running on the Union Pacific. It achieved great fame and notoriety on it May 26th, 1934, when it made its famous “Dawn to Dusk” travel between Denver, Colorado and Chicago Illinois – a distance of over 1,000 miles.

The Burlington Zephyr covered that distance in just thirteen hours!

Both the Zephyr and the M-10000 were featured attractions at the 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago, to which the Zephyr had made its record-breaking travel that day. During the Fair, the M-10000 was rechristened the Streamliner, marking the first appearance of the term in conjunction with the lightweight, high-speed locomotives they would become associated with for the next three decades. More than a million people would visit the Streamliner on its demonstration tour between February and May 1934, and the Zephyr would also attract similarly large crowds as well on its nationwide tour.

By 1936, the Union Pacific had introduced an evolved M-10001/2 pair of trainsets to its fleet with five new locomotives; the M-10001 boasted a more powerful 1200 horsepower Winton diesel engine while the M-10002’s set featured the 1200 horsepower diesel plus a 900 horsepower cab/booster. The Pennsylvania Railroad would introduce its own streamliner in the form of the GG1 in 1935 with its famed art deco framework and electric propulsion. Running in the more densely-packed northeast, the last GG1 was retired from service in 1983.

By the 1940s and the war years, most major railways in the country were embracing the usage of streamliners. Unfortunately for train enthusiasts, this golden age of speed and aesthetics would not last forever. One of the major issues with streamliners in particular were the articulated build of the trainsets; if one car had a problem, the entire train would have to be taken off the line for service and repairs, not just the individual car… and they were also becoming increasingly uneconomical for fuel usage. The last of the steam-powered streamliners would be gone by the early 1950s.

One of the biggest blows to streamliners came with the advent of speed caps introduced by the Interstate Commerce Commission, limiting trains to 79 MPH and thus depriving them of their greatest advantage over the very competition that had inspired their development in the first place: the automobile. By the 1950s, America’s network of interstate highways had begun to be developed, and with the nation’s automotive infrastructure advancing at a rapid rate, auto travel was quickly becoming more practical than train travel. The higher cost of fuel and upkeep was quickly making passenger rail economically unviable for rail companies.

The true death knell for the streamliner came from the advent of another competitor for high-speed travel; jet airliners began to enter service in the 1950s as well, making air travel an economically viable form of transportation between long distances. Between government regulations, high operating costs, and lower passenger volumes thanks to the competition from jet airliners and interstate automotive traffic, streamliners began to disappear from the railways. By 1971, the industry was so close to total collapse that Washington intervened, creating the National Railroad Passenger Corporation to subsidize passenger rail travel moving forward.

They do business today as Amtrak, a name anyone that has traveled by train in the last fifty years is sure to hear, often with great revulsion and disgust, particularly when taken in comparison to travel during the age of streamliners.

With the government now in control of passenger rail travel, we have all come to enjoy the efficiency of any wonderful Washington governmental bureaucracy. In addition to being chronically underfunded by the government, most of the routes Amtrak uses are kept up with funding from state legislatures which can make the bureaucratic headaches even more complex. Delays are frequent with the train service, and amenities compared to the luxuries of the streamliner years have been cut to almost nothing. It is, in effect, a horrid mode of transportation outside of highly urbanized corridors like the northeast.

Compared to its European counterparts, with their emphasis on public transport infrastructure spending, train service in the United States has become something of a laughingstock. But with global concerns over anthropogenic climate change and carbon emissions becoming a higher priority, the need for long-distance mass transportation has never been higher. It would suffice to say that Amtrak could use this moment in history to take a page out of the history books and look to its past to evolve into something modern rail passengers could embrace.